The right to remain silent paradox

The right to remain silent paradox

Admittedly, this is not my field of expertise, and perhaps the argument presented is ‘legally’ pointless. Nevertheless, it seems that the right to remain silent (5th Amendment in US Constitution, but widely present in most countries in the world) is paradoxical.

First a little history. Remember the Hollywood scene of a ‘cop’ making an arrest and his voice slowly fading out: “You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford one ….” Well, actually that’s the gist of the matter. Because if you can’t afford one, you probably won’t be able to use the right to remain silent. But more on this later.

Continuing with history. This so-called Miranda Warning – after the case of Miranda vs. Arizona – is generally believed to mean that one may remain silent and his silence cannot be used as an implication of guilt. It is used to tell the person of his or her right to remain silent after he or she is arrested. The key term is ‘after’ – that is, you are not read your rights for simple interviews, routine questioning, etc. Although this makes sense in Hollywood, it is quite an important detail.

Recently in US, although somewhat earlier in other countries (e.g. England and Wales), the meaning of the right to remain silent has been ‘adjusted’. The seemingly minor detail is exceptionally important. If you are not under arrest – and hence have not been read your Miranda rights – your silence can and will be used against you in a court of law! Hard to swallow? See this case of Salinas vs. Texas of 2013. What the ruling in principle says is that without your rights being read to you – i.e. prior to official arrest – you have to literally say that you are using your right to silence. And even then, if you do say something afterwards – say, because the question is whether you indeed are John Smith – your right to silence is revoked.

In a different case, accepting to be interviewed by the police, cooperating with it for whatever reasons, also results in giving up your rights. Determined under the Raffel ruling – Raffle vs. US – you cannot reclaim a right to silence once you decided to cooperate with the police.

What does this all mean?

Simply put, the right to remain silent is pretty weak. The police does not have to advise you of your rights prior to arrest – they can simply call you for questioning, at which stage your right to silence must be attested by yourself. If you have cooperated by then, you have also waived your right to silence afterwards. It makes sense to have a lawyer handy at all times now; not being able to afford one simply results in you not knowing what to say and when.

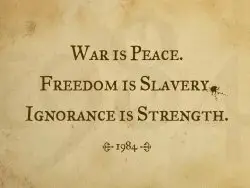

In other words, rather paradoxically, it is your right to silence that may end up in your disadvantage.

The implications of this are quite upsetting. It can mean that various legal, but rather obscure procedures can be used to trap the suspects. Though this makes great TV (e.g. Lie to me), it also makes your rights rather pointless! The Salinas vs. Texas clearly shows us that this pseudo-scientific approach to law, in fact both police and justice, is quite dangerous. As the Slate columnist Brandon L. Garrett poignantly observes:

If Salinas had answered the question by exclaiming that he was innocent, could police have reported that he sounded desperate and like a liar? … But if he doesn’t answer, at trial, police and prosecutors can now take advantage of his silence, or perhaps even of just pausing or fidgeting (source).

Finally, this is not an exclusively American phenomenon. In England, a similar approach is present. You may remain silent is the advice, but if some details you would like to use in court were not mentioned during your questioning, it may be used against you!