The Animal Farm paradox, or how we are all more equal than others

The Animal Farm paradox, or how we are all more equal than others

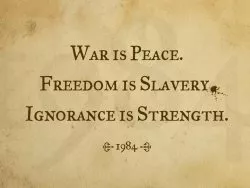

In the well-known and much repeated [amazon text=Animal Farm&asin=0451526341] by George Orwell [sidenote: should I really say who wrote the Animal Farm?], the paradoxical sentence “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others” is part of the cardinal rules set up by the (capitalist?)1 pigs. Certainly, this statement does not make any sense. And even more certainly, Orwell’s point was to point out an ‘evident truth’ – a political statement on dictatorial/totalitarian regimes which function through similar (even identical) espousals on equality. Some have noted that Orwell may have been pointing towards the subjective perspective of individuals on equality, though this is somewhat doubtful. Disregarding for a moment what Orwell’s intents were, there remains a dangerous paradox in Orwell, one that requires serious considerations.

Let us first examine what Orwell is about. A very brief synopsis of Animal Farm:

The animals unite themselves against the humans – they come to power – pigs and dogs start organising the farm – other animals slowly shift lower and lower in the possibilities of expressing their ‘newly acquired freedom’ – pigs resemble the humans

The problem Orwell makes sure we try to understand, is the problem of power in the traditional sense of a means of oppression. He seems to follow a well-known maxim: “Power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely” (attributed to Lord Acton, though earlier references exist in different forms) – and it is in this sense that the seizure of power by the pigs slowly develops into a corruption of their initial vision. It is not doubted by anybody that the initial intentions of the pigs was not to become corrupt, only that it was an outcome of their new position. Through possession of minimal power and the ensuing corruption, they tend to maximise their power which inevitably will lead to more corruption. So far, the matter is not really paradoxical.

The most notable points of Animal Farm are the gradual changes in the rules (The Seven Commandments), where exemptions are presented in a natural way (‘leadership needs to think and requires apples and milk to do so’). There is a level of Freudian ‘uncanny’ there – something is so familiar that it makes us feel uneasy about it. Don’t we also witness gradual exemptions for certain individuals, corporations, etc. in our world? Are we not slowly turning towards an Orwellian fable, where a certain group of people is being exempt from law that was meant to apply to everybody? Are we not witnessing exemptions in a similar vein? – No animal shall drink alcohol in excess. No animal shall sleep in a bed with sheets. It should not be surprising that the last commandment also adds an exemptive clause: ‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others‘.

In a Zizekian sense, are we not leading towards a prohibition on pleasure, precisely in that sense where pleasure functions as its own limit? Enjoy Coke, but make sure it is Diet Coke, because of high sugar and caffeine! Enjoy meat, but make sure it is free range and organic! And so also, Enjoy alcohol, but not in excessive amounts!

Orwell’s Parallels with Huxley

Orwell’s view or vision of the future becomes problematic once we contrast his writings with Aldus Huxley’s [amazon text=Brave New World&asin=0060850523]. In Huxley’s narrative [sidenote: I am not sure I would call this a dystopia, hence narrative] there are no commandments as such, everything flows into pleasure. But it is the pleasure itself that is problematic – everything is a spectacle, a point of laughter, of sexual desire. Even death is not something that saddens the onlookers. But there is nevertheless a similar undertone of critique between Huxley and Orwell – thought causes for their critique differs considerably.

Specifically, let us look at certain themes that have the same aim, but come from a different causal fear:

– Censorship: Orwell feared censorship; while Huxley feared that there would be no need for one as nobody would be interested in serious matter anyway as we would seek easily accessible entertainment.

– Transparency: Orwell feared we would be deprived of information; Huxley feared we would be overwhelmed/mesmerised by too much information.

→ Ultimately, Orwell feared we would not know political truths because they would be hidden from us; while Huxley feared that it would be accessible, but become irrelevant in the vast sea of all kinds of information.

In other words, what Huxley observed was that it was not the whip – that the pigs start using in the Animal Farm – that is the problem. Instead, it is the drug that makes one passive to his interests – soma (literally meaning body in Greek). In other words, Huxley identified pleasure with the decline of culture/civilization; and ultimately also freedom in the sense of being able to do that which we were meant to do without the obstruction into our interests. Nietzsche calls this becoming who you are! Interestingly, he calls the passive attitude the ‘last man’ (or Heidegger simply calls him Das Man).

Now to the really troubling part. If Orwell was right about the totalitarian regimes’ restriction of freedom by use of force; is it well-founded to say that Huxley was right about the liberal-democratic regimes’ restriction of freedom by use of entertainment/pleasure (he calls it “distraction” at some point, but entertainment seems to take the general tone)? And if that is the case, can we safely posit that the problem in the liberal-democratic regimes is not the restricting whip, but equality? But it is precisely here that we are turning a full circle back to Orwell – for equality no longer means ‘being equal among others’, but ‘being more equal than the others’, which furthermore is applied to each one of us. The World State as described by Huxley is nothing short of a state without internal politics – it is a 10 person dictatorship, which abolishes any political thinking. But in doing so, it also establishes a barrier between those within this World State and those outside of it – the Savage Reservation is filled with internal strife (i.e. it is inherently political).2 We are all in the process of espousal of some truth through which our ruin is made possible by not developing things of importance. And this article surely falls under the same rubric. In order not to be misunderstood, it is not my intention to promote anarchy, or some form of authoritarianism over liberal-democracy – but to think what liberal-democracy results to given the possibility of passivity as a culture/civilization, and perhaps find ways to overcome the inherent passivity.

Huxley’s letter to Orwell

In a letter from Aldous Huxley addressed to George Orwell, he states that his vision of the future is probably more correct. Interesting, though not at all surprising, is the convergence of our opinions. Then again, I am writing 75 years after the publication of [amazon text=Brave New World&asin=0060850523]. The particular passages that are particularly interesting to my analysis have been highlighted below:

Wrightwood. Cal.

21 October, 1949

Dear Mr. Orwell,

It was very kind of you to tell your publishers to send me a copy of your book. It arrived as I was in the midst of a piece of work that required much reading and consulting of references; and since poor sight makes it necessary for me to ration my reading, I had to wait a long time before being able to embark on Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Agreeing with all that the critics have written of it, I need not tell you, yet once more, how fine and how profoundly important the book is. May I speak instead of the thing with which the book deals — the ultimate revolution? The first hints of a philosophy of the ultimate revolution — the revolution which lies beyond politics and economics, and which aims at total subversion of the individual’s psychology and physiology — are to be found in the Marquis de Sade, who regarded himself as the continuator, the consummator, of Robespierre and Babeuf. The philosophy of the ruling minority in Nineteen Eighty-Four is a sadism which has been carried to its logical conclusion by going beyond sex and denying it. Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful. My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described in Brave New World. I have had occasion recently to look into the history of animal magnetism and hypnotism, and have been greatly struck by the way in which, for a hundred and fifty years, the world has refused to take serious cognizance of the discoveries of Mesmer, Braid, Esdaile, and the rest.

Partly because of the prevailing materialism and partly because of prevailing respectability, nineteenth-century philosophers and men of science were not willing to investigate the odder facts of psychology for practical men, such as politicians, soldiers and policemen, to apply in the field of government. Thanks to the voluntary ignorance of our fathers, the advent of the ultimate revolution was delayed for five or six generations. Another lucky accident was Freud’s inability to hypnotize successfully and his consequent disparagement of hypnotism. This delayed the general application of hypnotism to psychiatry for at least forty years. But now psycho-analysis is being combined with hypnosis; and hypnosis has been made easy and indefinitely extensible through the use of barbiturates, which induce a hypnoid and suggestible state in even the most recalcitrant subjects.

Within the next generation I believe that the world’s rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience. In other words, I feel that the nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four is destined to modulate into the nightmare of a world having more resemblance to that which I imagined in Brave New World. The change will be brought about as a result of a felt need for increased efficiency. Meanwhile, of course, there may be a large scale biological and atomic war — in which case we shall have nightmares of other and scarcely imaginable kinds.

Thank you once again for the book.

Yours sincerely,

Aldous Huxley

Edit 04/08/16: It has come to my attention while adapting this page for a new version of the layout, that a social critique summarised this post back in 1985! I am some 30 years late:

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egotism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy . . . In 1984, Orwell added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we fear will ruin us. Huxley feared that our desire will ruin us (Neil Postman, [amazon asin=014303653X&text=Amusing Ourselves to Death], p. vii).

You can get [amazon text=Animal Farm&asin=0451526341] and [amazon text=Brave New World&asin=0060850523] from Amazon.

Sign up for Paradox of the Day mailing list and please visit our Patreon support page.

- I am aware that it is meant as a satire to Bolshevik Revolution; but if you consider the amount of transactions going on in the book, you could easily confuse it for capitalism. Just an example, when Boxer is injured, the pigs tell the other animals that Boxer is going to the hospital, while he is being sold to a slaughter house.

- For those familiar with Carl Schmitt’s work, the relation between the two ‘orders’ is a curiously Schmittian one: the political categories are conditions for their existence – or to put it differently, the World State stands in directly antagonistic relation to the Savage Reservation.