Nietzsche and the Jews

“Don’t let in any more Jews! And lock the doors to the east in particular (even to Austria)!” – so commands the instinct of a people whose type is still weak and indeterminate enough to blur easily and be easily obliterated by a stronger race.”

Beyond Good and Evil, §251

Nietzsche and the Jews

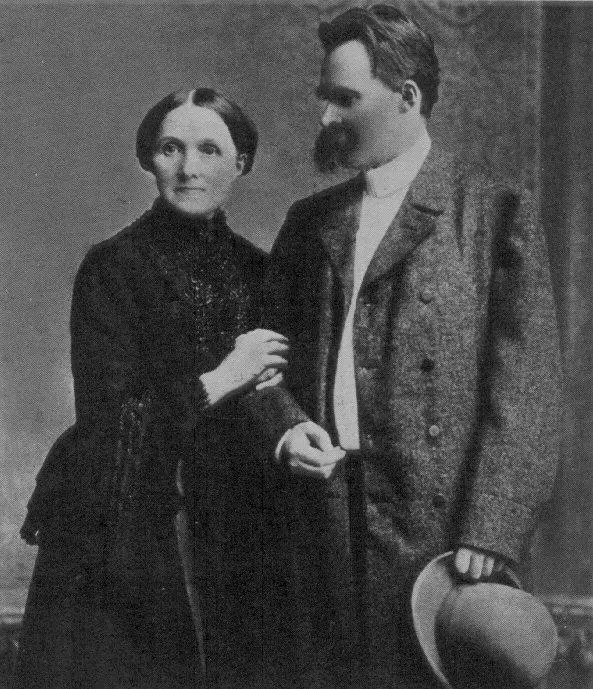

The place of Jews is notoriously controversial in Nietzsche’s body of work. Ever since his sister Elisabeth took charge of editing his manuscripts, there has been considerable disagreement on the extent of her own anti-Semitism imported to Nietzsche’s writing. The fact remains, however, that Nietzsche wrote of the Jews much earlier than his collapse in Turin – and indeed that [amazon asin=0521016886&text=The Antichrist] and [amazon asin=052169163X&text=Towards the Genealogy of Morality] manuscripts were largely finalised and underwent relatively few edits (though, of course, some edits were significant).

Regardless of the controversial status of Nietzsche’s body of work, it is without a doubt that what has been traditionally called ‘The Jewish Question’ (after Marx’s short essay in response to Bruno Bauer) is central to Nietzsche, even though the Jewish question is more politically laden than Nietzsche’s scope of analysis. It is equally without a doubt that Nietzsche’s position regarding the question remained uncertain despite the place of Jewish tradition in his work as early as [amazon asin=0521567041&text=Human All-too-Human], where for instance in §114 (The un-Hellenic in Christianity) he notes the difference between the Greeks and the Jews in their relation to god(s):

The Greeks did not see the Homeric gods as set above them as masters, or themselves set beneath the gods as servants, as the Jews did. They saw as it were only the reflection of the most successful exemplars of their own caste, that is to say an ideal, not an antithesis of their own nature. They felt inter-related with them, there existed a mutual interest, a kind of symmetry (Hollingdale translation).1

And yet, while Nietzsche remained uncertain of his views, the expressions about Jews did appear in his work. This is of course not to say that Nietzsche was unclear – quite the contrary. What I mean by uncertain is precisely in the lack of certain conclusions to be drawn, or specific actions to be taken regarding the Jewish question. In what follows, I aim to show why this uncertainty regarding the Jewish question is fundamental in understanding Nietzsche as an ‘anti-anti-Semite’. Doing so will help us to counter the accusations of anti-Semitism without resort to biographical episodes – largely found in his letters to friends and family. Instead, it should be possible to counter the arguments from his work – i.e. philosophically.

The philosophical framework of the Jewish question

When approaching the issue of anti-Semitism, it is important to keep in mind a fundamental distinction that enframes Nietzsche’s view of the Jews: the difference between the actuality of the state of affairs, and the genealogical roots of the actuality. That is to say that there is in Nietzsche, on the one hand, an accusation of anti-Semitism towards individuals (like Bernhard Förster, Elisabeth’s future proto-Nazi husband) and likewise defence of individual Jews – and likewise their extensions into political mode of behaviour and the social relations that are at the heart of the Jewish question: the rampant anti-Semitism of his day and the actual Jewish communities seeking emancipation. On the other hand, and opposed to the previous, there is the priestly Judaic tradition that was inscribed into Protestantism – something that Nietzsche was at pains of pointing out to his contemporaries.2

Before proceeding with Nietzsche’s anti-anti-Semitism, let me briefly note what is meant by the priestly Judaic tradition with a reference to his [amazon asin=052169163X&text=Towards the Genealogy of Morality] §I.7:

The anti-Semitic attitude incorporates the very thing it aims to negate. Share on XThe history of mankind would be far too stupid a thing if it had not had the intellect [Geist] of the powerless injected into it: – let us take the best example straight away. Nothing that has been done on earth against ‘the noble’, ‘the mighty’, ‘the masters’ and ‘the rulers’, is worth mentioning compared with what the Jews have done against them: the Jews, that priestly people, which in the last resort was able to gain satisfaction from its enemies and conquerors only through a radical revaluation of their values, that is, through an act of the most deliberate revenge [durch einen Akt der geistigsten Rache]. Only this was fitting for a priestly people with the most entrenched priestly vengefulness. It was the Jews who, rejecting the aristocratic value equation (good = noble = powerful = beautiful = happy = blessed) ventured, with awe-inspiring consistency, to bring about a reversal and held it in the teeth of the most unfathomable hatred (the hatred of the powerless), saying: ‘Only those who suffer are good, only the poor, the powerless, the lowly are good; the suffering, the deprived, the sick, the ugly, are the only pious people, the only ones saved, salvation is for them alone, whereas you rich, the noble and powerful, you are eternally wicked, cruel, lustful, insatiate, godless, you will also be eternally wretched, cursed and damned!’ . . . the slaves’ revolt in morality begins with the Jews: a revolt which has two thousand years of history behind it and which has only been lost sight of because – it was victorious . . . ([amazon asin=052169163X&text=Towards the Genealogy of Morality], §I.7).

Anti-Semitism has at its core a priestly attitude – but what does that mean? Nietzsche argues here that there is a continuity to be found between the tradition of opposing the masters and the contemporary slavish nature of blind following of popular positions (security through state, anti-Semitism, etc.) – the powerless in the first sentence are thus to be taken seriously, those who could not protect themselves. This continuity between the Jewish tradition and contemporary slavish nature is what he terms priestly Judaism – it is structured around fear and ressentiment. Priestly Judaism requires the other for negation, its own position is only that of negation of the other. As irony would have it, the anti-Semitic attitude thus incorporates the very thing it aims to negate – namely, the priestly Judaic tradition. Instead of affirmation of life, the anti-Semite negates the other as a precondition of their being.

Nietzsche’s letters to friends and family

Let us now turn to the actuality of the state of affairs. There is ample evidence of Nietzsche’s dismissal of anti-Semites in his private letters. For example, he writes to his sister towards the end of December 1887:

One of the greatest stupidities you have committed—for yourself and for me! Your association with an anti-Semitic chief expresses a foreignness to my whole way of life which fills me ever again with ire or melancholy. . . . It is a matter of honor to me to be absolutely clean and unequivocal regarding anti-Semitism, namely opposed, as I am in my writings. I have been persecuted in recent times with letters and Anti-Semitic Correspondence3 sheets; my disgust with the party (which would like all too well the advantage of my name!) is as outspoken as possible, but the relation to Förster, as well as the after-effect of my former anti-Semitic publisher Schmeitzner, always brings the adherents of this disagreeable party back to the idea that I must after all belong to them. . . . Above all it arouses mistrust against my character, as if I publicly condemned something which I favoured secretly—and that I am unable to do anything against it, that in every Anti-Semitic Correspondence sheet the name Zarathustra is used has already made me sick several times (as quoted in Kaufmann, [amazon asin=0691160260&text=Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist], p. 45).

Similar letters of condemnation of anti-Semitism were written to his friends and family. Some letters show the internal conflict that Nietzsche has with anti-Semitism as it destroys his relationship with Elisabeth. He writes to Franz Overbeck:

'Anti-Semitism is the reason for the great rift between myself and my sister' - Nietzsche Share on XThis accursed anti-Semitism . . . is the reason for the great rift between myself and my sister (as quoted in Yovel, [amazon asin=0415095131&text=Nietzsche and Jewish Culture] (edited by Jacob Golomb), p. 121).

The most telling case of dismissal of anti-Semitism in Nietzsche’s private life is a brief correspondence (in 1887) with the editor of Der Hammer4 – Theodor Fritsch. Nietzsche ends the first letter (a very amiable one in tone, in contrast to what is to follow in the following letter) with the following request:

Please publish a list of German scholars, artists, poets, writers, actors, and virtuosi of Jewish extraction or intraction! That will be a valuable contribution to the history (and criticism!) of German culture (Yovel, [amazon asin=0520083180&text=Nietzsche, Genealogy, Morality: Essays on Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals] (edited by Richard Schacht), p. 220).

In the following letter, after receiving some anti-Semite propaganda from Fritsch, Nietzsche more openly dismisses him:

I hereby return your three Correspondence Sheets with gratitude for the trust that enabled me to get a glimpse of the concoction and confusion of principles upin which theis strange movement of your is founded. That being the case, I request that you no longer continue to privilege me with these mailings: I do fear finally for my patience (ibid.).5

The private letters are of course especially noteworthy because they establish the difficulty that it brings to his personal life, his close relation with his sister6, his alleged love for Cosima Wagner, his close friendship with Wagner himself prior to their falling apart, etc. Nietzsche did not want to be association with the anti-Semitic movement. He did not simply oppose it for the sake of opposition, or as something unconcerning to him; quite the opposite, these letters show how deeply anti-Semitism affected him on a personal level.

- Die Griechen sahen über sich die homerischen Götter nicht als Herren und sich unter ihnen nicht als Knechte, wie die Juden. Sie sahen gleichsam nur das Spiegelbild der gelungensten Exemplare ihrer eigenen Kaste, also ein Ideal, keinen Gegensatz des eigenen Wesens. Man fühlt sich mit einander verwandt, es besteht ein gegenseitiges Interesse, eine Art Symmachie.

- In fact, one could go as far as to say that the allegory of The Madman in Gay Science §125 is meant precisely at this end – the Christian god is dependent on the Judaic god; Christian anti-Semitism (and likewise the Islamic one) is thus at its very core a dubious endeavour.

- I will return to these briefly.

- Coincidentally, Nietzsche gives his Götzen-Dämmerung, ‘Der Hammer Redet’ as subtitle.

- Yovel gives further examples of letters written days after his collapse in Turin – the so-called Twilight Letters – which equally show his struggle with anti-Semitism. An example:

Although so far you have demonstrated little faith in my ability to pay, I yet hope to demonstrate that I am somebody who pays his debts—for example, to you. I am just having all anti-Semites shot. - Despite academic dismissal of Elisabeth, it is very clear that Nietzsche loved his sister – despite her anti-Semitism.