Is there a paradox in Kant’s ethics? Must we tell the truth?

Is there a paradox in Kant’s ethics? Must we tell the truth?

There has been quite some misunderstanding in undergraduate courses on Kant’s moral philosophy. The general argument presented there is that Kant as a deontological thinker places greater value on duty/rules than on anything else.1 So the general argument that is presented to undergraduates in order to make them think further, is that Kant would under no circumstances allow lying. Those who study philosophy have certainly heard the famed axe-man scenario: A well-known murder knocks on your door, standing there with an axe in his hands, and asks where your children are so he could murder them. Now according to the general interpretation of Kant, one is not allowed to lie about this and has to answer truthfully, and lead this axe-man to his children’s certain death.

That’s the worst reading of Kant possible, perhaps it is even better never to have read him at all; and I am very curious how my students end up with this belief when entering my classroom. Perhaps it is because of that brief interchange with Benjamin Constant; though most probably it is because of taking the easy way out instead of thinking further on the issue. So in what follows, I will try to posit why Kant’s moral philosophy is largely misunderstood.

Phenomenal and noumenal realms

Just as when reading Aristotle’s ethics, one should first recognise that at the heart of his moral philosophy is not simply life, but ‘good life’; or that the core of Nietzsche’s moral philosophy comprises of revaluation (and thus not rejection); so too with Kant, the first realisation should recognise that his moral philosophy centres around human autonomy (and not simplistically duty). Keep this in mind, as I will return to it later. Duty certainly plays a fundamental role, but this is only insofar as it furthers our autonomy in actions. The reason for this is that the world is comprised of causal relations. Kant engages with Aristotle’s ethics and rejects the emphasis on virtue – one can be virtuous, but unlucky. One could do everything to further his virtuousness, but still fall prey to the causal relations in the world, where his hands are tied. So in order to break from this inane causality of the world (the ‘phenomenal’) one has to regard the categorical imperative as duty/law – put differently, the possibility of being autonomous (i.e. free) depends on the very causal relations in the phenomenal realm, and in order to free oneself from the phenomenal realm, one needs to regard the categorical imperative as duty/law.

The problem that Kant faces is that the categorical imperative is not within the phenomenal realm – it corresponds with the thing-in-itself, the ‘noumenon’ (i.e. it is independent of our awareness).2. So what Kant in fact faces is the challenge on how to make this dual relation work – how to account for autonomy in light of the causal relations of the world (the phenomenal realm) and the irretrievable notion of categorical imperative (the noumenal realm)? Or how is one to even abide a law that is independent of our awareness of it? I have to point out at this stage that we are not simplistically dealing with armchair philosophy here. Kant in fact engages with an incredibly important question in ethics that can be translated into, for instance, our contemporary organisation of international institutions. Are the United Nations declaring universal laws of human rights? Or are these laws dependent on particular cultures and thus cannot be universal? What when time passes, and we realise that some laws were too restrictive on some populations (African American slavery is but one of many examples)?3 How are we to reconcile these ethical points with political action? Are states responsible for their actions even if they follow rules (such as the UN forces in Srebrenica)? I do not have clear answers to these questions, but it is all the more important to recognise that we are not simply dealing with some issues that are removed from reality.

So how is one to abide a law that is independent of our awareness? Kant’s position is, at least to a degree, to remove the law from its pedestal. The law is no longer imposing itself on the individual action through precise rules, but rather presents itself as a sudden realisation of what is right – each situation is a unique circumstance. In turn, the possibility of human autonomy would be meaningless if laws imposed themselves without taking into account what our unique historical conditions were. We may certainly follow certain guidelines in our daily routine, we may even think of how we would act in different situations, but each situation is different (it is not every day that a murderous axe-man appears in front of my door). Ultimately, the historical condition necessitates a take on the law as something appearing to us as a ‘sudden realisation’.

We can see already that Kant is not prescribing duties to be obeyed indiscriminately. But, Kant continues, this must also apply to the categorical imperative. The categorical imperative belongs in the noumenal realm and cannot be known as such. Even though Kant gives several formulations – or perhaps, precisely because Kant gives several formulations – the categorical imperative functions according to the same type of sudden realisation rather than set divine rules.4 This is indeed to say that the categorical imperative is an ‘empty’ set of duties/rules – empty precisely in that sense of not having commandments as we are used to. There is no duty/rule to not lie (or steal, or kill, etc.) precisely because the categorical imperative belongs to the noumenal realm which is not approachable by human rationality – it is a realm that is independent of our awareness, we cannot experience it, let alone understand which duties/laws are in it. A position that one must tell the truth to the murderous axe-man, then, is not only simplified, but also utterly false.

A clear objection is certainly that Kant himself stipulated several examples of duties – to not deceive another, for instance. The reason for this was not some inane theological position that lying is wrong, that it is one of the commandments that has come down from god, etc. Kant’s ethics is concerned with logical consistencies. He thus gave an example of borrowing money without any intent of paying back. To deceive another is considered morally wrong because if this rule were to be followed by everybody (universalised, as the first formulation of the categorical imperative stipulates), there would be no possibility to borrow money any longer – nobody would be lending money if they were to know that there is no possibility of them getting it back. To put it in Kantian terms, this would lead to a contradiction.5 My claim is that, even though Kant gave specific examples, they were only meant as to highlight the importance of the resulting contradiction; his aim was to emphasise that to follow the categorical imperative cannot lead to a contradiction. The examples he uses are thus not examples of specific duties; but rather examples of resulting contradictions. Or to put it differently, there are no knowable maxims prior to moral actions.

Centrality of autonomy

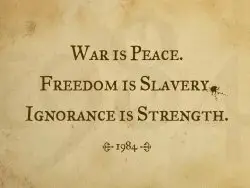

It is now time to return to Kant’s moral philosophy as revolving around autonomy. It is clear from our axe-man example that we are never free to answer either positively or negatively – we are not free because we are restrained by the actions of the murderer. The sad reflection here is that we have forgotten how to approach freedom without directly being involved with choice. Especially in the Western societies, freedom is first equated with whether we have a choice between various positions, so that we may freely choose one of the many positions that are presented to us. To be sure, there is nothing wrong with choices (though being presented with too many choices may lead to paralysis); the problem is that this is not the type of freedom that Kant had in mind.

For Kant, freedom is essentially passive – freedom consists of a predisposition. This may sound paradoxical, but it is not (unlike my blog would suggest). Kant’s view is in fact not even unique. Already in Aristotle we find an ethical theory that has more to do with our disposition or attitude towards the contingency of events, than it does with choices between alternatives. For Aristotle, virtue was something one attains through actions – if one acts bravely in face of danger, for instance. But such action is not something that one has chosen to do, though it is still the case that one has done so freely. The essential point here is precisely that such action has come about from a disposition that one has, perhaps, learnt or has taken to be his duty. This is exactly where the categorical imperative (in all its formulations) comes to play such a crucial role – it creates the disposition according to which one will act. But as you note, it does not require any choices to amount to freedom. Quite the contrary, one’s actions further cement the disposition that would lead to future actions.

The great danger here is when one cements a disposition to such a degree that his/her action is no longer a free act because it follows an already common predisposition that has been taken to be one’s own – in no sense would such actions be called free; at best they would be something specific to a particular actor, further ‘enslaving’ them into a particular role. What is required, therefore, is to remain open to the categorical imperative in each action (indeed, it is very demanding!).

What this tells us about the example of the axe-man is that acting according to the maxim ‘do no lie’ renders us ‘automatons’ rather than autonomous. In Kant’s ethical theory, the only possibility of acting morally is by regarding it one’s duty to remain autonomous in each specific situation. But it also tells us that a hypothetical situation that is discussed in classrooms is almost meaningless – at best, it makes one aware that one can only marginally be prepared to an axe-man at the doorstep; at worst, it wholly distorts our ability to understand Kant. A hypothetical situation necessarily misses the very point that Kant is making; namely, that a decision on an action is dependent on an actuality of the situation – i.e. that only the person standing in front of the axe-man can act according to the categorical imperative (and thus tell the truth or lie), only that person can have the ‘sudden realisation’ mentioned before, only that person is actually free.6

This is indeed to say that no action can be taken as a moral standard for other ‘similar’ situations – an act of bravery in face of danger, for instance, is not a specific enough situation to exert moral authority over other ‘similar’ situations. Telling the truth (or lying) to the axe-man similarly loses all standards of morality precisely because that moral action is only specific to that situation. The reason for this is that any action is by necessity in the phenomenal realm (while the categorical imperative is in the noumenal one).

The strange thing is that we are all aware of this. We may not have had a murderous axe-man at our doorstep, but I am certain we all have that awkward moment when we acted in the same way as we did in what we thought to be similar circumstances as the past ones, only to realise how foolish we must have looked to our friends and passers-by.

Three further possibilities/solutions

There are several other possibilities to answer the question: must we tell the truth to the murderous axe-man? The first one actually comes from someone I dismissed early on in this article, Benjamin Constant:

“It is a duty to tell the truth. The notion of duty is inseparable from the notion of right. A duty is what in one being corresponds to the right of another. Where there are no rights there are no duties. To tell the truth then is a duty, but only towards him who has a right to the truth. But no man has a right to a truth that injures others.” The πρωˆτον ψενˆδος here lies in the statement that “To tell the truth is a duty, but only towards him who has a right to the truth” (my emphasis).

The last sentence is self-explanatory; though it should be mentioned that Kant did not accept this ‘solution’ as such. His answer consists in pointing out that one is responsible for consequences of lying while telling to truth relieves them thereof.

“if you lied and said he was not in the house, and he had really gone out (though unknown to you) so that the murderer met him as he went, and executed his purpose on him, then you might with justice be accused as the cause of his death. For, if you had spoken the truth as well as you knew it, perhaps the murderer while seeking for his enemy in the house might have been caught by neighbours coming up and the deed been prevented”

This is certainly a very weak argument, for while you may feel guilty over telling a lie, and indeed indirectly cause the harm done – you would feel much worse looking at the axe-man doing what he came to do.

Another possibility is to answer without lying, which would be fully in line with Kant’s ethical theory. One can imagine the following conversation:

Murderous axe-man: “Hey, buddy. Sorry to bother you so late at night, but eh…. where are your kids?”

You: “Excuse me?”

Murderous axe-man: “Well, you know…. I’d like to kill them. I’ve just cleaned my axe, it’s nice and shiny, see?” The axe-man grins. “They won’t feel a thing, promise. So where are they?”

You: “I’d rather not answer to you, if it’s all the same to you. I love my kids, and I would miss them if you’d kill them.”

Murderous axe-man: “Oh, common. Please, tell me.”

You: “I am sorry, it is against my moral principles.”

Murderous axe-man: “Well, if you are moral man, you ought not to lie and tell the truth. Also, if you are a Christian man, you ought to tell the truth – it’s one of the commandments, you know. Right there in Leviticus 19:11.”

You: “It also says, you shouldn’t kill.”

Partner/kids call 911 in the meantime. (Or 999, or 112, depends where you are living really.)

Murderous axe-man: “Well, yeah, but I am not a Christian.”

You: “For ‘not a Christian’, you seem to know your Bible very well, how did you know where it says so exactly.”

Murderous axe-man: “I’ve been to your neighbours yesterday, and they didn’t let me kill their kids. So I had to go look it up. I mixed the houses today, so I am standing in front of you now.”

You: “So if I don’t tell you where my kids are, you will just go away and mix houses again tomorrow and bother one of the other neighbours?”

Murderous axe-man: “No man, I am for real this time, I am going to kill you if you do not tell me.”

You: “Wow, chill man. All I am saying is that you are using double standards here. And it is you who mixed up the houses.”

Murderous axe-man: “You are making me angry. Either tell me where your kids are, or I am going to kill you!”

You: “Relax dude. It’s just a little weird that you would want to kill my neighbours’ kids, then my kids and now me. At least, there was that ‘killing kids’ pattern before. How do I fit into this?”

Murderous axe-man: “You are in the way, that’s how.”

You: “Look behind you.”

Someone fires a gun at the murderous axe-man.

Murderous axe-man: “I’m dead.” (in the sound of the game Worms).

(This very well might be the worst script ever written.)

Last option would be to slam the door in his face.

Sign up for Paradox of the Day mailing list and please visit our Patreon support page.

- For Aristotelians, good ethics is about virtue, whereas for utilitarians good ethics follows the simple (simplistic?) doctrine ‘greatest happiness of the greatest number of people’.

- Kant uses noumena and thing-in-itself almost always interchangeably; for the purpose of this article, I do the same even though there are minor differences.

- Recall that the US Constitution starts with the inalienable rights of all men. But at the same time, almost all of the Founding Fathers held slaves – which in the Constitution are defined as “persons held in service or labor”. It may sound logical today to have largely abolished slavery worldwide (though other forms persist), but it is certainly plausible that we are still restrictive on parts of the population without our own awareness of it.

- There are three formulations, and they are very nicely detailed in various places online. I have no major objections to the formulations that you would find on Wikipedia, for instance. Instead of reproducing the analysis here, though, I would like to stress that the interchange with Constant that you find on Wikipedia as well, is not the final word on the matter and only specifies the criteria addressed by Constant.

- In less specific terms, lying leads to deceitful language, where everything uttered could or could not be a lie, making all of our communication rather senseless – quite possibly, we would entirely stop communicating with one another.

- In this (and not much else), Kant’s ethical theory is strangely close to Nietzsche’s notion of overcoming – only through overcoming can we in fact be free.