The Grandfather Paradox – “I’m My Own Grandpaw!”

The Grandfather Paradox – “I’m My Own Grandpaw!”

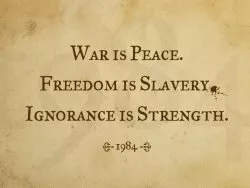

The grandfather paradox is quite straightforward, and has many varieties. In the simplest version: if you were to build a time machine and use it to travel back in time and kill your grandfather before your parents (usually one of them) were consummated, you wouldn’t have been born in order to build a time machine – and thus travel back in time in order to kill….

Now for the less straightforward version, and for this one we need to look at one of the greatest science fiction writers: Robert Heinlein. There is much to be said about Heinlein, and his fans most probably will not like my simplicity, but the most relevant aspect for the grandfather paradox is his “—All You Zombies—” (get it from [amazon asin=0312875576&text=Amazon]). This version revolves around a character by the name of Jane, at least until Jane becomes a man….

The narrative is twisted, so here follows a chronological order to point out the paradox in question (spoiler alert, I guess):

1945 – a girl (Jane) is dropped off at an orphanage.

1963 – Jane is seduced by an older man (or they fall in love); but the man disappears some time later, and leaves Jane pregnant.

1964 – Jane gives birth to a baby girl by a caesarian cut (incidentally, this has nothing to do with Julius Caesar, despite some myths circulating about this). Interestingly enough, Jane is told by the doctor that she has an odd condition: “Ever hear of that Scottish physician who was female until she was thirty-five?—then had surgery and became legally and medically a man? Got married. All okay.” So it appears at this stage that Jane in fact has both sexes, both still premature, but she could get pregnant. Well, they had to make Jane into a man (let’s call him Joe, though the story refers to him as “unmarried mother”). Some weeks after the surgery, Jane’s/Joe’s daughter disappears from the hospital.

1970 – ‘Unmarried mother’ Joe frequents a bar, and accepts the wager of the Bartender that in his profession no story is new to his ears. The Bartender is a time-traveler, and after some conversation takes our Joe to the past, so that he can take revenge on the older man that seduced him when he was still Jane.

1985 – Joe becomes a time-traveler and goes into the past, where he meets a man calling himself ‘unmarried mother’.

1993 – Joe reflects on his life.

Just to be sure, the Bartender is in fact Joe (and Jane). The point of this short story is quite complex (in the sense that it is not as easily deducible as it could be). Heinlein was a staunch individualist. This short story exemplifies his views by taking a position on the grandfather paradox. In several scenes from the story, there is a song playing: “I’m My Own Grandpaw!” and it seems that Heinlein wants to illustrate that, though perhaps physically impossible, this is in fact very possible if we forget that (minor?) detail. Jane/Joe/Bartender are all one person. You could take this to mean that you are responsible for all your actions; though I would find it more convincing that Heinlein’s point is that you can’t lose sight of your own doings. That in order to achieve anything, you have to know what you are. Inevitably, we all achieve something and have this knowledge to some extent. And not in the contemporary sense of knowing where you are from in order to know where you are going (‘I’m still Jenny from the block’, right?). This sense of reflexivity, of self-knowledge as philosophers like to put it since Socrates, is the simple satisfaction one would need in order to sleep at night. The ending lines of the short story are very powerful to that effect:

The Snake That Eats Its Own Tail, Forever and Ever [i.e. Ouroboros] . . . I know where I came from—but where did all you zombies come from? [Notice here that ‘zombies’ is not used in Hollywood sense of walking dead; but more pragmatically that we all could be dead to the narrator, because there are no other characters in his story]

I felt a headache coming on, but a headache powder is one thing I do not take. I did once—and you all went away. [Again, notice how the narrator refers to the disappearance of the others; one might think that that powder has not worn off still]

So I crawled into bed and whistled out the light.

You aren’t really there at all. There isn’t anybody but me—Jane—here alone in the dark. [And here we have it again]

I miss you dreadfully!

One may wonder what this solipsism is for. And that would be an interesting topic to look into. But that would take us away from the paradox, and into philosophy (probably Wittgenstein’s [amazon asin=0061312118&text=Blue Book]). So instead, let’s have fun with this song:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7AvG6q_iTcA

On a less pleasant note, as much as I like Paul Verhoeven, it is really unfortunate that he went against [amazon asin=0441783589&text=Heinlein’s version] of Johnny Rico (or rather, Juan Rico), and made him into an average white American (played by Casper van Dien – who must have some Dutch ancestry like the director). Can you imagine [amazon asin=B008Y6TYQ8&text=Starship Troopers] with a Filipino Rico (my choice: Edwin San Juan)? There, I made it pleasant again.

Sign up for Paradox of the Day mailing list and please visit our Patreon support page.

2 Responses

[…] See also the Grandfather Paradox analysed here. […]

[…] After ending one post on solipsism, it seems that some form of qualification is necessary in order for it not to be regarded as paradoxical. A general argument for a solipsist inconsistency is that upon making his (usually his!) statement, the solipsist returns home to his loving wife / children / family. There is, in other words, some paradoxical relation between the statements of a solipsist and his behavior. However, this seems to be an inadequate presentation to the solipsist inconsistency. At its least, the solipsist could simply answer that his family (loved ones) are all part of his imagination, and taking care of them is what his mind asks him to do. So how can we view solipsism as both a framework that does not involve selfishness, but as something fruitful for our being? And can we reach this conclusion without resorting to a paradoxical statement? […]