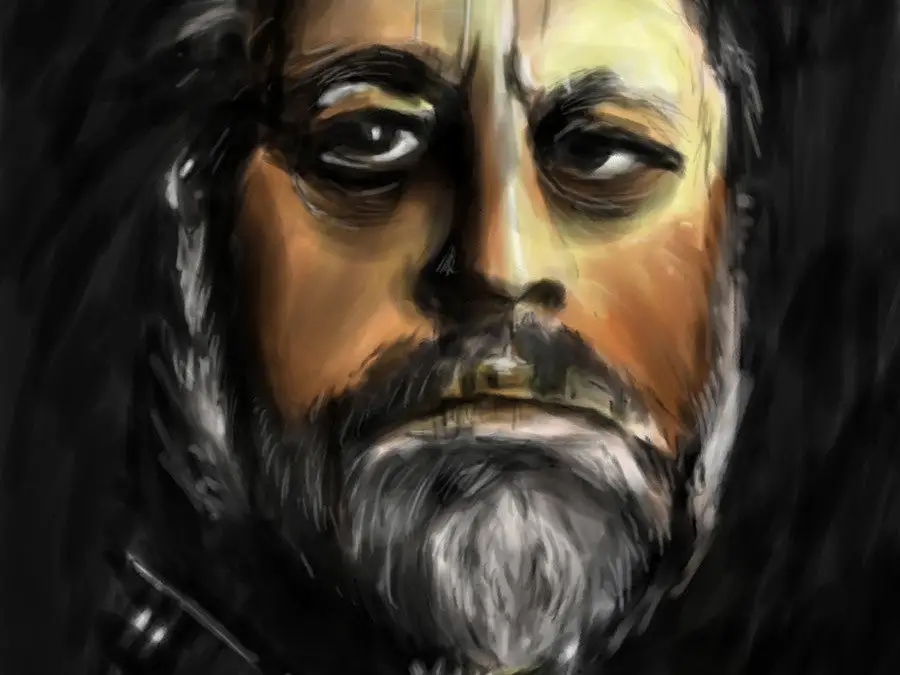

Some thoughts on art – part 3 (Zizek again)

Slavoj Zizek by Clowntree

Some thoughts or art – part 1 (Zizek)

Some thoughts on art – part 2 (Arendt)

My last written thoughts on art in this blog were roughly one and a half years ago. That’s a very long time to come back to a certain text; unless, of course, if you are an academic and for some reason are drawn to particular texts more than others. I picked up my copy of The Fragile Absolute and started reading, only to be captured once again on Zizek’s analysis of art. My estimation is that I am tired1 of his politics, but also that I am still unclear about the role of art in any of my own thoughts. Aesthetics escapes me almost entirely, and yet I feel drawn to a view of ‘aestheticising’ the political space.

This time, the passage that caught my attention was a little further than the previous one (cf. first part of ‘Some thoughts on art’):

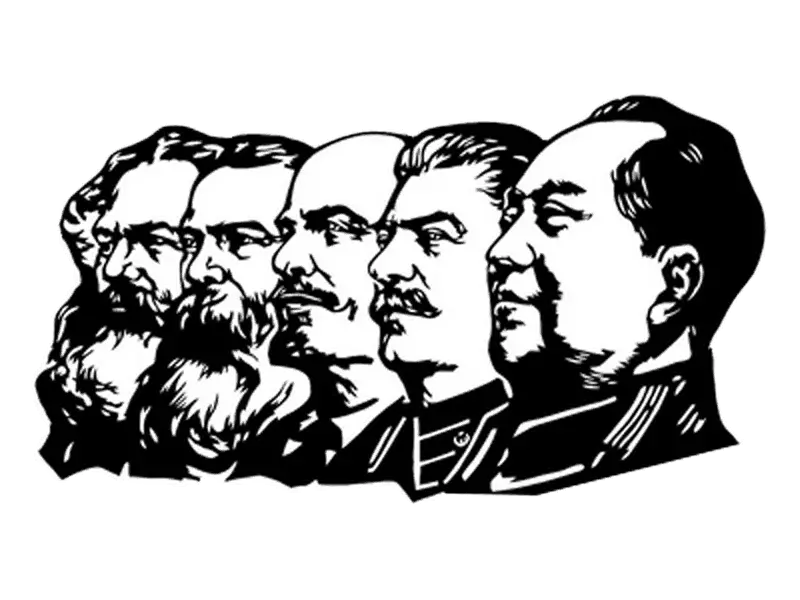

one is tempted to assert the contemporaneity of artistic modernism with Stalinism in politics: in the Stalinist elevation of the ‘wise leader’, the gap that separates the object from its place is also brought to an extreme and thus, in a way, reflectively taken into account. In his key essay ‘On the problem of the Beautiful in Soviet Art’ (1950), the Soviet critic G. Nedoshivin claimed:

Amidst all the beautiful material of life, the first place should be occupied by images of our great leaders. . . . The sublime beauty of the leaders . . . is the basis for the coinciding of the ‘beautiful’ and the ‘true’ in the art of socialist realism.18

How are we to understand this logic which, ridiculous as it may seem, is at work even today, with North Korea’s Kim Yong Il?.19

How indeed? The basic premise in Zizek’s view is that both the Stalinist leader and artistic modernism function according to the same logic – they elevate the persona of the object of desire to a domain that cannot be approached in another way than through a poetic license. That is, both the Stalinist leader as well as modernist art, cannot be spoken of other than through an abstract ideal – an understanding of both rests on an understanding not of the person (or specific work of art), but on the the understanding of the person/art as an ideal that they represent. Browsing any art gallery, or asking any art student, the description of the work of art is almost never in terms of the work itself – it is always in terms of representation of a universality in guise of particulars. Take this example of Tate Modern in London:

The Material Worlds wing looks at the ways in which artists engage with diverse materials. Since the early twentieth century, artists have not felt confined by the media traditionally associated with fine art. Instead they have embraced a range of new materials, exploring a variety of forms and textures, from the precious to the throwaway and from the handcrafted to the mass-produced. (source)

Such a description aims to capture the universality of the fine art by appealing to a break from tradition, and yet presents the works themselves as particular instances (‘from the precious to the throwaway’). It is in this sense that our understanding of the relation between the Stalinist Leader and artistic modernism are only approachable through a notion of an abstract ideal. To this end, Zizek utilises Lacan’s notion of the Lady of the Court – that is, a person who is elevated to an ideal, whereby her femininity as such can only understood as an ideal (i.e. no longer understood even as an object of desire, let alone as a subject).

This abstract character of the Lady indicates the abstraction that pertains to a cold, distanced, inhuman partner – the Lady is by no means a warm, compassionate, understanding fellow-creature:

By means of a form of sublimation specific to art, poetic creation consists in positioning an object I can only describe as terrifying, an inhuman partner. The Lady is never characterized for any of her real, concrete virtues, for her wisdom, her prudence, or even her competence. If she is described as wise, it is only because she embodies an immaterial wisdom or because she represents its functions more than she exercises them. On the contrary, she is as arbitrary as possible in the tests she imposes on her servant.21

And so, Zizek asks, “is it not the same with the Stalinist Leader? Does he not, when he is hailed as sublime and wise, also ‘represent these functions more than he exercises them’?” These rhetorical questions are not meant to deprive whatever is left of the Stalinist Leader – it is doubtful that many found the Soviet Leaders as beautiful (in the sense of aesthetically pleasing beauty).2 The point instead is that precisely because of the elevation of the Stalinist leader onto an unapproachable pedestal, their representation of beauty only exemplifies the “terrifying, an inhuman partner”. What we learn from Zizek (or rather Lacan) here is that the leader’s embodiment of beauty permits the capricious and arbitrary acts.

Thus the price the Stalinist Leader pays for his elevation into the sublime object of beauty is his radical ‘alienation’: as with the Lady, the ‘real person’ is effectively treated as an appendage to the fetishized and celebrated public Image.

But such a fetishisation of the public figure, is precisely what is at stake with all political functionaries. Zizek recounts an anecdote of Kim Yong Il – that he actually died in a car crash and is now being replaced by a double for the few public appearances – to point out exactly that there is no need for the actual persona of the Stalinist Leader as such, that their embodiment of beauty is in fact all that matters. That is in fact to say that the Stalinist leader does not possess any power as such (though we know this already from Foucault), and it is his representation that carries all the power with it.

It is in this same sense that we can understand artistic modernism – it reduces beauty to a purely functional role. Or to put it differently, just as all political functionaries are replaceable, for as long as the representation of their beauty remains; so too with the actuality of the work of art, as long as it is approached merely as functional. In both cases, the replaceable Stalinist Leader and artistic modernism – both in actuality ‘ugly’ objects, are only approachable through a representation of beauty.

To conclude with Zizek’s own words, a typical rhetorical question: “Is not this practice of elevating a common vulgar figure into the ideal of Beauty – of reducing beauty to a purely functional notion – strictly correlative to the modernist elevation of an ‘ugly’ everyday excremental object into a work of art?22”

Zizek’s Notes:

18. Quoted from Julia Hell, Post-Fascist Fantasies, Durham, NC: Duke University Press 1997, p. 32.

19. Kim Yong II is hailed by the official propaganda as ‘witty’ and ‘poetic’ – an example of his poetry: ‘In the same way as sunflowers can blossom and thrive only if they are turned up and look towards the sun, people can thrive only if they look up towards their leader!’

20. Jacques Lacan, The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, London: Routledge 1992, p. 149.

21. Ibid., p. 150. Translation corrected.

22. It is against this background that one should appreciate the early (Soviet) paintings of Komar and Melamid, as exemplified in their ‘Stalin and the Muses’: they combine in one and the same painting two incompatible notions of beauty: ‘real’ beauty – the classicist notion of Ancient Greek beauty as the lost ideal of organic innocence (the Muses) – and the purely ‘functional’ beauty of the Communist leader. Their ironically subversive effect does not lie only in the grotesque contrast and incongruity of the two levels, but – perhaps even more – in the suspicion that Ancient Greek beauty itself was not as ‘natural’ as it may appear to us, but conditioned by a certain functional framework.

Citations are from Zizek’s The Fragile Absolute, part of The Essential Zizek (which for once I think is correctly identified by publishers as essential [insert author] series).

Some thoughts or art – part 1 (Zizek).

Some thoughts on art – part 2 (Arendt).

Sign up for Paradox of the Day mailing list and please visit our Patreon support page.

- Tired does not mean uninterested or opposed, it just means tired.

- Then again, how many still remember who Nixon’s sex symbol (pdf) was?