4 Examples of Oxymora in Romeo and Juliet – a study guide

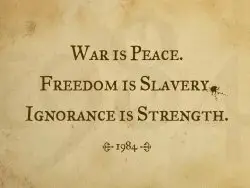

We are thus presented with the drive of mankind to do both good and bad. It would be a folly to consider there to be in Shakespeare a battle between good and bad/evil. There is, in fact, no explicit mention of ‘evil’ in the play, while the term ‘good’ is utilised dozens of times in a variety of manners by Shakespeare: “good friend”, “good cousin”, “good friar”, “good fellow”, “good heart”, etc. The point is that we should not consider the struggle between good and bad to be on a moral landscape. My claim here is, once again, that the struggle between good and bad in Romeo and Juliet is but an internal struggle between the drives. As mentioned above, both drives are a necessary component of being human – the struggle itself is what defines being human as such. Shakespeare’s insight is that the possibility of death is immanent were one to dominate the other: “And where the worser is predominant, / Full soon the canker death eats up that plant”. While the domination of the ‘worser’ drive leads to death, Shakespeare does not imply that it is possible for the ‘good’ drive to dominate at all times. His claim seems to be fundamentally different: what should dominate is the struggle itself – the internal conflict of the drives.

4. “Was ever book containing such vile matter so fairly bound”

The framework of analysis of oxymora does not stop with Romeo, Juliet, or mankind in general; it can be extended further into other fields that I mentioned in the introduction. With this fourth examples, let us have a look at how this framework fits with aesthetics. A careful reader will note that I have already used this passage (from Act 3.2) before in setting up the framework; we have come a full circle. There is, of course, a set of Euphuistic contrasts pertaining to aesthetics in that particular passage:

Beautiful tyrant! fiend angelical!

Dove-feather’d raven! wolvish-ravening lamb!

In these oxymora there is, next to the already mentioned moral judgments, a definite aesthetic judgment on the part of Juliet. The contrast is between what is beautiful and ugly; though beauty and ugliness should not be restricted to a physical appearance only. The aesthetic judgment is in fact on another level of duality between the outer and inner beauty, between the physical and the mental, psychological, emotional, etc. beauty.

This is most clear in the depiction of Romeo as a “dove-feather’d raven”. Romeo is seen by Juliet comprising of a dual appearance – a disguise that further intensifies her internal struggle. Ravens are of course dark, following a deep contrast to doves which are white. So Shakespeare seems to play with this duality of darkness and brightness of Romeo that Juliet perceives: she sees him as a dove that very well may be a raven. What this tells us in particular is that Juliet’s perception of Romeo is both on the physical appearance (“beautiful”, “angelical”) as well as an insight into his inner workings (“tyrant”, “fiend”) – disputing the notion that ‘love is blind’ that is often attributed to Romeo and Juliet.1 Quite the opposite, Juliet is fully aware of Romeo’s misgivings and reading her lines closely, by focusing on oxymora present, it is quite clear that there is a tremendous amount of internal struggle (albeit often mixed with tremendous ambivalence).

There is more to Shakespeare’s “Was ever book containing such vile matter so fairly bound?” Does this phrase not sound a lot like a more recent one: ‘Don’t judge a book by its cover!’ Most media2 find the origin of this phrase to date to the 1860s. I think it safe to assume that despite the precision of the phrase, the sentiment behind it is much older. Certainly in Shakespeare, this sentiment is equally on the distinction between the outer and the inner.

It is equally safe to assume that next to ‘the vile content of a fairly bound book’, the Euphuistic contrasts preceding it testify to Juliet’s internal struggles. It should be recalled that this particular passage comes after Juliet hears the news of Romeo killing her cousin (by this time they have agree to get married). So what Juliet undergoes is a deeply internal struggle between the aesthetically/externally beautiful Romeo whom she loves, and the mentally/internally vile Romeo that she hates – an internal struggle between her desire for Romeo and her repulsion towards his acts. Once again, familial loyalty only plays a secondary role.3

Conclusion

To briefly conclude, it is my view that Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet can be analysed by following a particular framework of internal struggles of its characters. These internal struggles are the result of internally opposing drives that Shakespeare so eloquently presented by the frequent use of oxymora. It is my claim that the result of these struggles is ultimately irrelevant to Shakespeare. What Shakespeare seems to emphasise is the importance of the struggle itself – the moment the struggle is abandoned to whichever drive, though Shakespeare is more strongly emphasising the ‘worser’ drive, so too comes death. And is this not the end of Romeo and Juliet when they decide to abandon the struggles that they were facing?

Sign up for Paradox of the Day mailing list and please visit our Patreon support page. Also, consider visiting our Amazon shop.

- And with good reason too, after all, Romeo’s friends are laughing at his expense in Act 2.1 for his blind love.

- The often cited first record of the phrase is of the June 1867 issue in the newspaper Piqua Democrat that reads as follows: “Don’t judge a book by its cover, see a man by his cloth, as there is often a good deal of solid worth and superior skill underneath” (source). George Eliot supposedly says something to that effect in her The Mill on the Floss (1860), though I have not read that book (source).

- There is a wholly different approach possible, while maintaining the same framework – namely the contrast between the aesthetic judgment as an everlasting experience and the fleeting moments of active life that cannot be reduced to aesthetics. Indeed, I am saying here that one can construct a certain basis for political theory on this play. But that is a wholly different and a more difficult matter to accomplish than I set out to do.